Should people without disabilties play parts in film of people with disabilties?

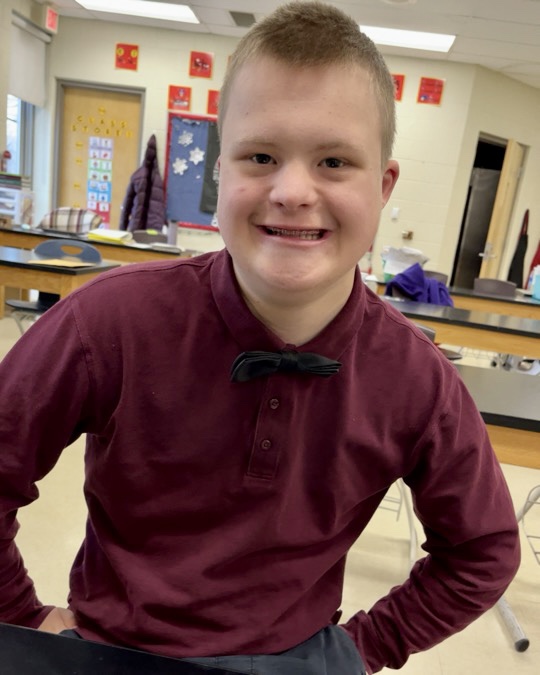

There have been some impressive performances of such cases. But then I thought, if Wil were an actor, would he be hired to play any part but of the person with Down syndrome? That would be summed up in two letters: NO. And if he were an actor, how would I feel about a person without Down syndrome playing his part? How would he feel? I would be appalled on many levels. No matter how much that actor studied, how would they really know? Who better to play the part, to raise true awareness, and to give a paying job to, than someone who lives it.

In today’s age, what does disability representation in film look like? There is definitely what coined by Stella Young as “inspiration porn.” As a society, are we as progressive as we claim to be? It’s definitely something to give thought to. So I did some research. Then I wrote about (see below) for my Special Education class (please feel free to comment, I’d love to hear thoughts):

Time to Share the Mic: Authenticating the Voice of Disability in Film

Turner Classic Movies (TCM) played a double feature every Sunday this past July – a total of 10 movies for the month – showcasing people’s experiences with disabilities. The series, which coincided with Disability Pride Month, went as far back as the silent film Deliverance (1919) about Helen Keller and her teacher, Anne Sullivan. This early 20th-century film’s symbolism of ignorance and knowledge – one wore a white robe, the other black, and both urged Helen to follow them – was ahead of the times. The real Helen Keller and Anne Sullivan made an appearance in the film. The TCM series starter was The Best Years of Our Lives (1946), wherein three war veterans returned to their hometown “who are all in different states of physical and mental distress after the war” (Fields, 2023). One of the veterans is played by a real-life war veteran, Harold Russell. Russell lost both of his hands in a wartime incident, and having the choice between plastic prosthetic hands and steel hooks, he chose steel hooks. Russell became quite adept at using the steel hooks and eventually made a training film for soldiers who had lost both hands (Sevaro, 2002). Director William Wyler, a veteran himself with severe hearing loss due to his service, saw Russell’s training film and advocated hiring Russell. Russell had never had acting lessons, and Wyler stopped producer Samuel Goldwyn from arranging them. “This was a rare case of a person with an actual disability playing a character with a disability” (Fields, 2023).

Fast-forward the film reels of time to the present day and we will find that “significant depictions of disability on film and television shows have nearly tripled over the past decade compared with the previous 10 years”(Bahr, 2021). Per a Nielson study of among 3000 titles (from television and movies) from 1920 to 2021 nearly 70% of the content inclusive of disability was in film (Nielson, 2021).

So that is great news for the authentic voice of actors with disabilities to be heard, right? In film-speak, that would be called a long shot. Only 1.9% of all speaking characters in the top films of 2022 had a disability, according to an August 2023 report published by the University of Southern California (USC) Annenberg Inclusion Initiative (Heasley, 2023). The report states that “there has been no change in the representation of characters with disabilities since this community was included in our reporting across top films from 2015. Characters with disabilities are consistently missing in film.”(Smith, et al., 2023).

With an increase of disability portrayed in film, but with less than 2 percent of speaking characters with disabilities in recent top films, who is the voice of the disabled? Have we reverted back to the silent film days of Deliverance? The answer is, non-disabled actors are speaking for the disabled. Nearly 70 Academy Award nominations and 27 wins were given to non-disabled actors for playing disabled roles. Yet, only three actors with disabilities have won Oscars: The aforementioned Harold Russell, as Best Supporting Actor in 1947 for The Best Years of Our Lives, Marlee Matlin, who is deaf, as Best Actress in 1987 for Children of a Lesser God and most recently Troy Kotsur, as Best Supporting Actor in 2022 for CODA (Brownworth, 2023).

Non-disabled actors are clearly lauded, and applauded, for their portrayals of persons with an actual disability as is evidenced by the overwhelming number of nominations and Academy Awards given to non-disabled actors in relation to disabled actors. “Even though the number of disabled characters continues to increase, approximately 95 percent of those roles are still portrayed by actors who do not have disabilities,” said Lauren Applebaum, Senior Vice President of Communications at RespectAbility (Bahr, 2021).

And what of the content of the increased portrayals in film of people with disabilities? Consider what Stella Young, who spends her day in a wheelchair, coined as “inspiration porn” in her 2014 Tedx Talk:

The little girl with no hands drawing a picture with a pencil held in her mouth. You might have seen a child running on carbon fiber prosthetic legs. And these images, there are lots of them out there, they are what we call inspiration porn. (Laughter) And I use the term porn deliberately, because they objectify one group of people for the benefit of another group of people. So in this case, we’re objectifying disabled people for the benefit of nondisabled people. The purpose of these images is to inspire you, to motivate you, so that we can look at them and think, ‘Well, however bad my life is, it could be worse. I could be that person.’ But what if you are that person? I’ve lost count of the number of times that I’ve been approached by strangers wanting to tell me that they think I’m brave or inspirational, and this was long before my work had any kind of public profile. They were just kind of congratulating me for managing to get up in the morning and remember my own name. (Laughter) And it is objectifying. These images, those images objectify disabled people for the benefit of nondisabled people. They are there so that you can look at them and think that things aren’t so bad for you, to put your worries into perspective (Young, 2014).

If such inauthentic portrayals of disability have the power to shift human emotions, imagine how hard it is to unravel decades of film that have trained us to think about how disability should be portrayed. “When disability is a part of a character’s story, too often content can position people with disabilities as someone to pity or someone to cure, instead of portraying disabled individuals as full members of our society,” said Applebaum. (Bahr, 2021).

Rather than placing a non-disabled person’s bias on such portrayals, or portray people with disabilities as flawed or inspirations, a boost to authentic inclusion and diversity could be made by taking actions like Wyler in The Best Years of Our Lives; advocating for a person with an actual disability playing a character with a disability. Moreso, creating space for writers and directors behind the camera who have first-hand experience living with a disability. “The inclusion of disabled talent does not happen by accident. It is critical to have representation behind the scenes to ensure better and more authentic representation on screen,” said Appelbaum. “We need people with disabilities in a position to influence storylines and narratives, help make decisions about casting and talent, and represent the disability community throughout the creative process” (Nielson, 2022).

That’s exactly why some filmmakers and actors with disabilities are taking matters into their own hands by creating films such as Crip Camp and Peanut Butter Falcon. Crip Camp is a “groundbreaking summer camp for teens with disabilities. Crip Camp is the story of one group of people and captures one moment in time. There are hundreds, if not thousands, of other equally important stories from the Disability Rights Movement that have not yet received adequate attention.” Crip Camp’s release in 2020 marked the start of a campaign “whose goal was to use the film as leverage to create change for people with disabilities.” Crip Camp stands “by the creed of nothing about us, without us. For too long, too many were excluded, and it is time to broaden the number of voices and share the mic”(CripCamp.com, 2020). The idea for Peanut Butter Falcon began with a conversation between Zack Gottsagen, an actor who has Down syndrome, and his friends and screenwriters, Tyler Nilson and Michael Schwartz. Nilson shared with Gottsagen “that even though he was talented and had been studying acting for years, there just weren’t many roles written in Hollywood for actors with Down syndrome (or any disability) and that there was a very small chance that he’d ever get an opportunity to play a major role.” Gottsagen replied, “Well … you guys make movies, why don’t you write one and I can be in it?! We can do it together!” (Schwartz & Nilson, 2019).

There is reason to be hopeful that, as Gottsagen so aptly stated, “we can do it together!” More films with authentic disability representation have recently been released such as A Quiet Place, All the Beauty and The Bloodshed, CODA, Creed 111, and Netflix’s Rising Phoenix, Sex Education, and Special (Fraser, 2023).

Just maybe, we are realizing that “we need more relatable, middle ground, diverse disabled characters” (MediaTrust, 2019). Bobby Farrelly, director of Champions, a 2023 movie with a predominate cast of actors with disabilities, said, “We’ve become aware of how hard it is for disabled actors to get parts in movies because they don’t read for parts that aren’t disabled, so when the character is disabled, it should go to a disabled actor” (Heasley, 2023).

When non-disabled actors are applauded and awarded for their roles as the disabled, and when audiences applaud themselves with feel-good cheers of inspiration porn, or when the emotional wheels of pity are churned in scenes of people with disabilities marginalized as flawed, broken, or lesser versions of themselves – these are the reels of superficial progress. “We’re so busy believing we are being progressive…that we’re stuck in a rut, having lost sight of the fact that to progress means to move forward” (Zacharek, 2023). It’s time to shine a light on where the cast, crew, and audience have long followed a dark cloak of ignorance and celebrated it as knowledge. It’s time to shed light on the bigger picture. It’s time to share the mic.