Wil jumped onto the tube without hesitation.

Wil’s friend CJ, who we were visiting, propped himself on the tube next to Wil. Elizabeth laid down on the opposite side. CJ’s dad, Randy, asked if they were ready. All three gave a unanimous thumbs up. Randy fired up the boat and CJ’s mom, Cheri, was already expertly snapping pictures. Heavy clouds loomed; we wanted to tube as much as possible before the storm hit.

With Wil’s apparent confidence, Randy took the tube over some higher waves. Wil’s smile never wavered.

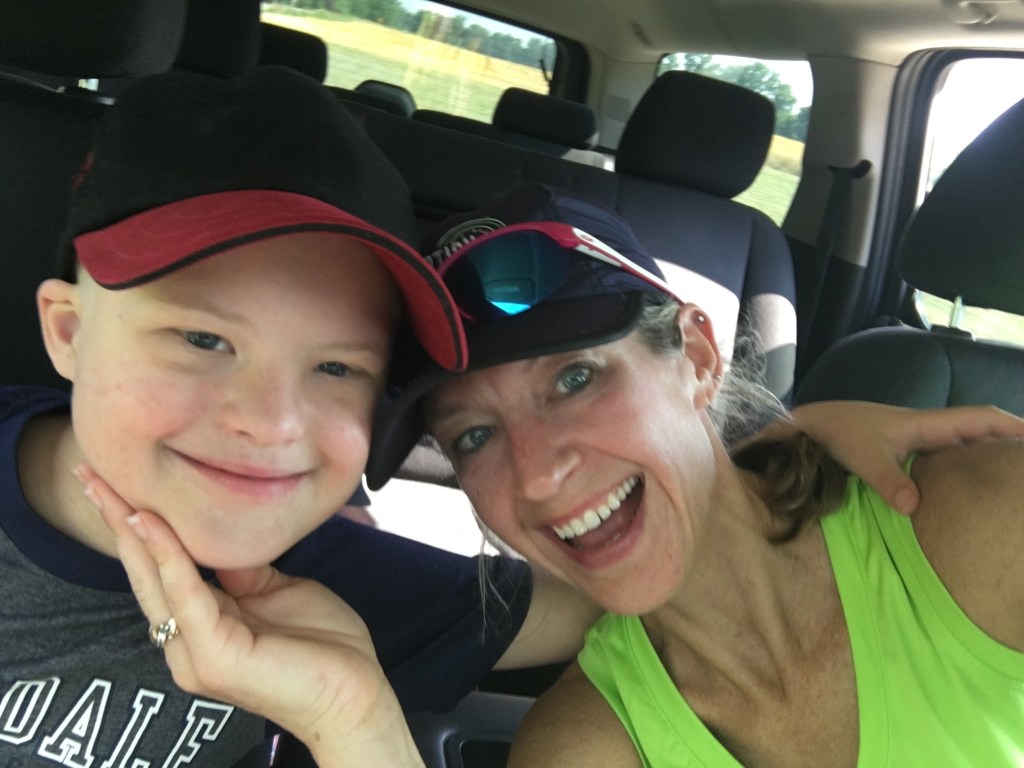

Last year’s tubing expedition took loads of coaxing to get Wil on the tube. It was Cheri who was finally successful. She climbed on the tube wearing her sunglasses. She told Wil she didn’t want to lose them, so the tube would stay right next to the boat. Wil inched his way onto the tube next to Cheri. He had a tight grip and winced at every slight movement.

Once Wil secured himself next to Cheri, he looked around the lake in awe. He couldn’t believe it! He’d made it onto the tube. After crossing that threshold, Wil never looked back. His bravery had clearly stuck with him into the next summer.

CJ, who will be a junior in high school this year, gives daily weather reports which he started during the pandemic. His weather reports became so popular that the local news has also broadcast them. CJ is a daredevil with watersports, is on the school’s marching band and bowling team, and shoots a mean 3-pointer. CJ, like Wil, has Trisomy 21, the most common form of Down syndrome. CJ recently started strength training and flexed his biceps for us. CJ asked Wil to join him in a few push-ups. Wil jumped right in with him. It became clear Wil needs to improve his core and upper body strength to do proper push-ups, but he saw CJ do it, so he knows he can do it too with time and practice.

All of CJ’s interests may or may not match Wil’s, but it’s important for Wil to see what can be done by a slightly older peer. When Wil was a toddler he watched his sisters, Elizabeth and Katherine, swim in the lake. He wanted so badly to swim like they did but he didn’t like how the bottom of the lake felt on his feet. Even with water shoes, he was hard to convince. One day he put on one of his sister’s bathing suits thinking he could magically swim. He quickly found that wasn’t so.

My parents, who live on the lake, kept walking Wil to the steps that led into the water. Little-by-little, step-by-step, he eased in. With time, encouragement and practice, mixed with the desire to swim like his sisters, he learned that he didn’t need magical powers. Now when he steps into the lake and jumps on a raft, his smile never wavers.

Wil doesn’t have to sink repeated 3-pointers to have value (though he’s sunk a few). However, each new jump he achieves adds value to his life. There is no magic behind it — it’s role models like Katherine and Elizabeth, my parents and friends like CJ, Cheri and Randy plus a dose of desire, patience and leaps of faith.

The smile on the other side of the leap, though…that’s all magic.